What is IDH?

Overview

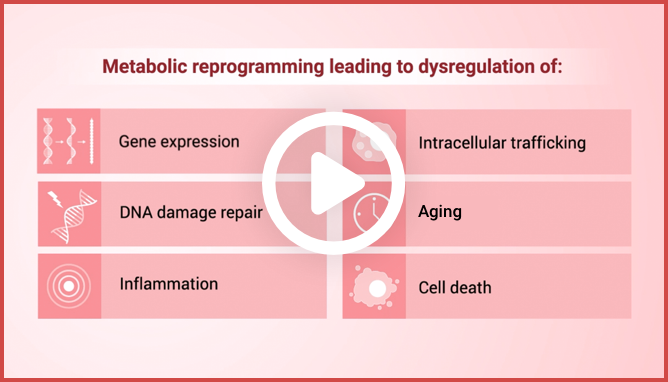

IDH1 and IDH2 mutations cause metabolic reprogramming that results

in dysregulation of4:

Gene expression

Intracellular trafficking

DNA damage repair

Aging

Inflammation

Cell death

Differences Between IDH1

and IDH2

Differences Between IDH1 and IDH2

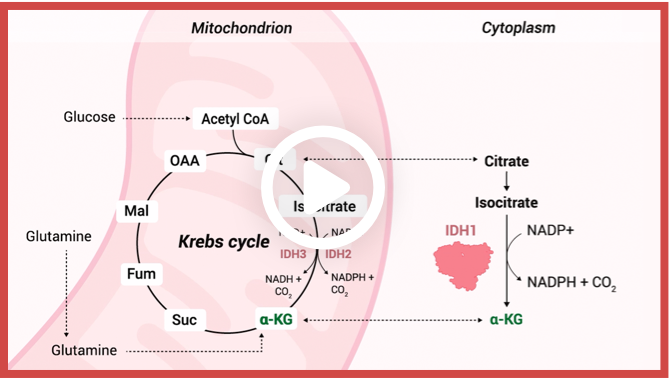

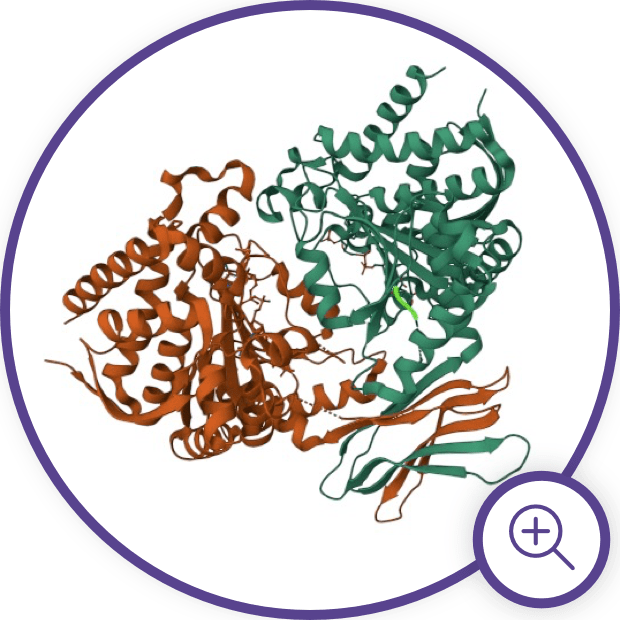

Enzymatic reactions catalyzed by wild-type IDH isoforms convert isocitrate to α-KG.1

IDH Enzyme Structure and

Gain-of-Function Mutations

mIDH Impact on Cellular

Differentiation via Epigenetic

Changes

Neomorphic activity of mIDH produces high intracellular levels of 2-HG and leads to epigenetic changes that interfere with myeloid differentiation.2,9

mIDH Impact on Immune

System Tumor Response

Additionally, emerging research has unveiled the impact of increased 2-HG levels and its influence on CD8+ T cells in anti-tumor responses.15 2-HG has been found to affect CD8+ T cell function, leading to inhibited proliferation, impaired degranulation, reduced production and release of interferon-ϒ, altered glycolysis, and impaired lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) function within these cells.15 Overall, this impairs the cancer-killing ability of T-cells and allows tumor proliferation.15

IDH mutations are just the tip

of the “iceberg”10–15

Explore video clips on the

function of IDH1 and the

impact of mutation1,3,16–18

Explore video clips on the

function of IDH1 and the

impact of mutation1,3,16–18

Malignancies Associated with

IDH Mutations

Mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 are seen in a variety of cancers, including AML, MDS, IDH-mutant glioma, and cholangiocarcinoma, thus reinforcing the key pathogenetic role of these mutations.3 IDH3 mutations are less common in cancer, and the impact of IDH3 mutations in cancer is still under investigation.3

mIDH is considered an early “driver” mutation in MDS and becomes more frequent as the disease progresses to AML.2,4,5,21 Mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 are present in 6% to 16% and 8% to 19% of patients with newly diagnosed AML, respectively.22

Malignancies associated with IDH mutations.1,3,19,20

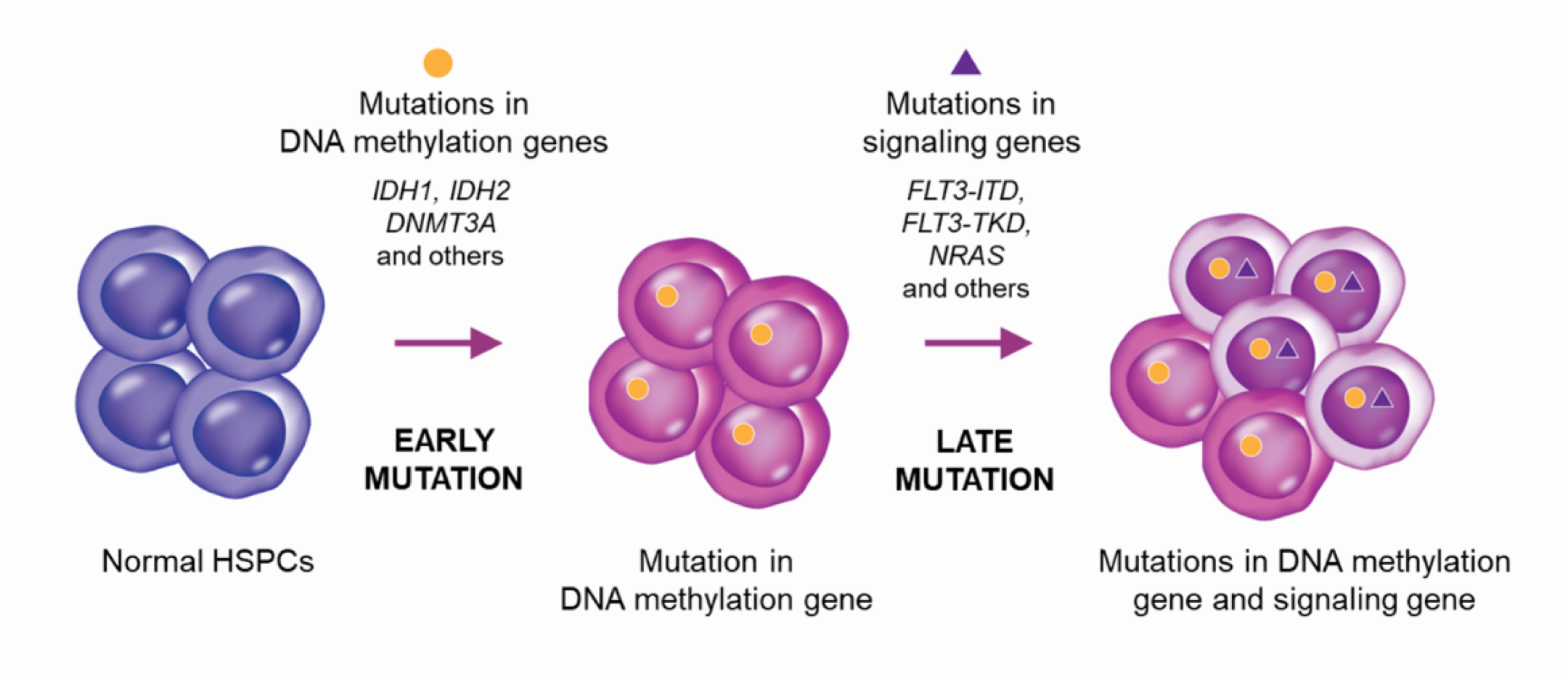

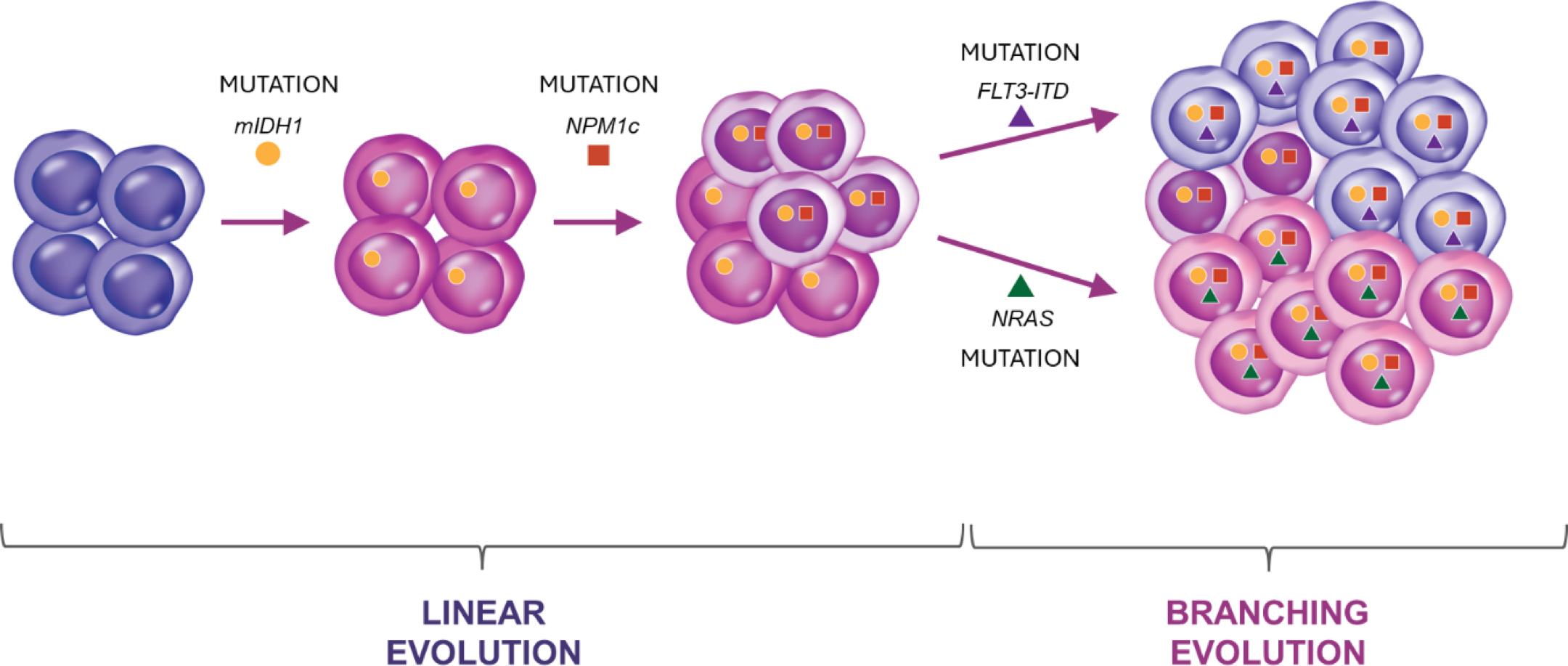

Genetically, AML progression entails successive accumulation of mutations, which tend to occur in a specific order with respect to biological pathways.23-26 Mutations in DNA methylation and other epigenetic genes (e.g., DNMT3A, IDH1/2) tend to occur early, while mutations in signaling genes (e.g., FLT3, NRAS) generally occur later.23-26 Analysis of clonal evolution in AML has revealed that early mutations in DNA methylation/epigenetic genes, including mIDH1 and mIDH2, are typically present in the main clone, while subsequent mutations, such as those in signaling pathway genes (e.g. FLT3 and NRAS), often emerge as secondary clones.25, 26

Clonal evolution in AML.23,26

Clonal evolution can occur in both linear and branching patterns, with signaling mutations often occurring after a branch point.26

Example of clonal evolution of mIDH1 AML, with mIDH1 representing the main clone, and the subsequent emergence of an NPM1-containing clone through linear evolution followed by emergence of FLT3 and NRAS secondary clones through branching evolution. Since mIDH1 is present in the main clone, it is present in all descendant cells in the NPM1, FLT3-ITD, and NRAS-secondary clones.26

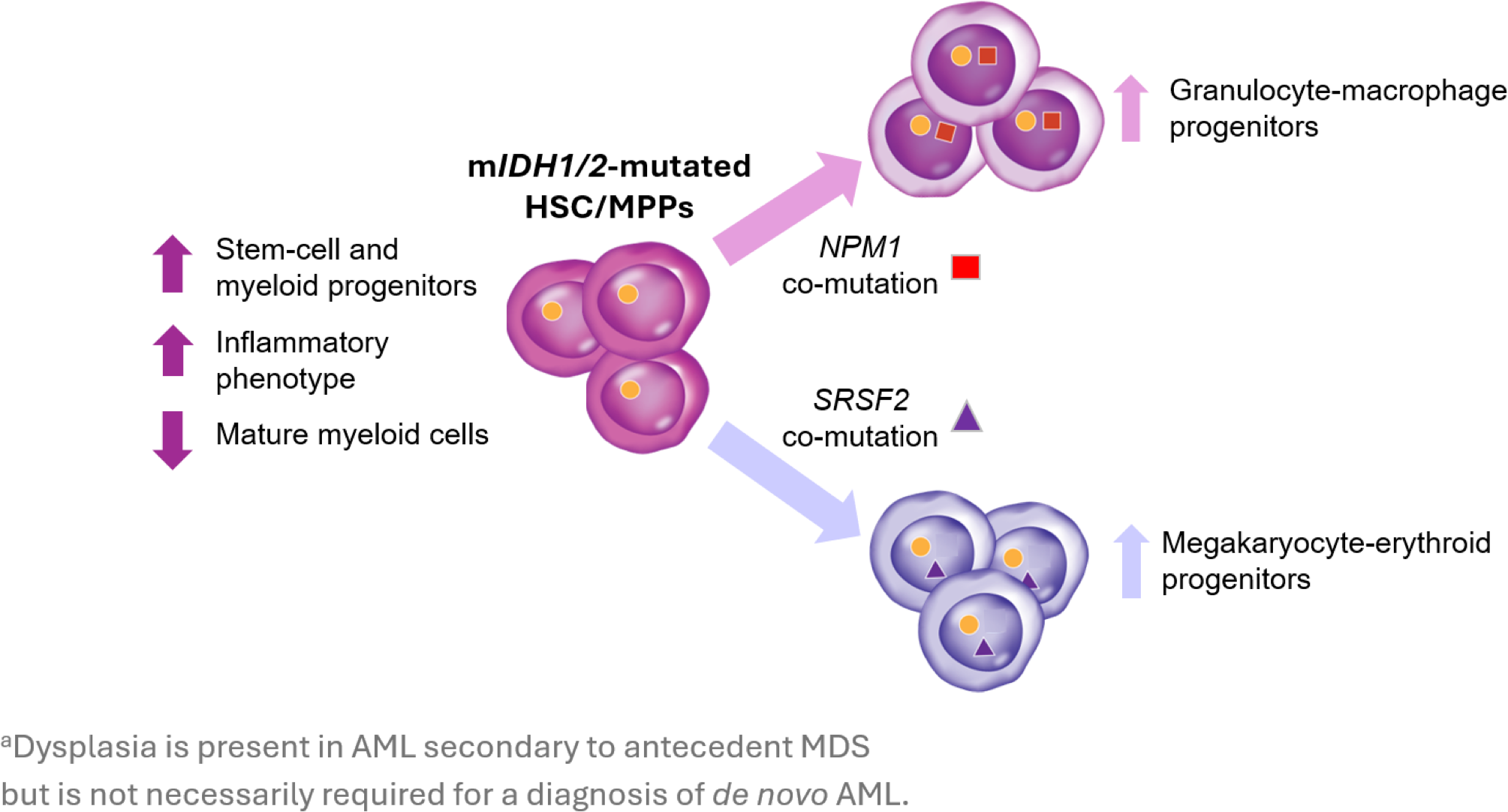

A recent study explored the transcriptomic phenotypes associated with mIDH1/2 AML, demonstrating that mIDH is associated with an increase in progenitor-like cells, a reduction in mature myeloid cells, and an increased inflammatory transcriptional phenotype. The presence of co-mutations with mIDH1/2 was shown to also impact transcriptional phenotype, with co-mutations in NPM1 and SRSF2 biasing hematopoiesis towards the granulocyte-macrophage and megakaryocyte-erythroid lineages, respectively.27

Transcriptional phenotypes associated with IDH mutations and co-mutations in NPM1 and SRSF2.27

Evaluation of patients with mIDH1/2 AML who relapse demonstrates that mIDH1 and mIDH2 are usually stable between AML diagnosis and relapse.28,29 However, there are cases in which mIDH1 or mIDH2 is present at diagnosis and disappears at relapse, and conversely, is not present at diagnosis but appears at relapse.28 These findings support the need for testing both at diagnosis and after relapse.

Stay in the Know

Keep up to date on the latest in

IDH science from leading experts.

References:

1. Losman JA, Kaelin WG. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):836-852. doi:10.1101/gad.217406.113 2. Testa U, Castelli G, Pelosi E. Cancers. 2020;12(9):2427. doi:10.3390/cancers12092427 3. Al-Khallaf H. Isocitrate dehydrogenases in physiology and cancer: biochemical and molecular insight. Cell Biosci. 2017;7:37. doi: 10.1186/s13578-017-0165-3. 4. Pirozzi CJ, Yan H. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(10):645-661. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00521-0 5. Thol F, Weissinger EM, Krauter J, et al. Haematologica. 2010;95(10):1668-1674. doi:10.3324/haematol.2010.025494 6. Jin J, Hu C, Yu M, et al. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100206. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100206 7. Waitkus MS, Diplas BH, Yan H. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(2):186-195. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2018.04.011 8. RCSB Protein Data Bank website. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3MAP. Accessed May 18, 2023. 9. Pan D, Rampal R, Mascarenhas J. Blood Advances. 2020;4(5):970-982. doi:10. 1182/bloodadvances.2019001245 10.Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, et al. Science. 2013;340(6132):622-626. doi:10.1126/science.1234769 11. Kernytsky A, Wang F, Hansen E, et al. Blood. 2015;125(2):296-303. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-10-533604 12. Molenaar RJ, Wilmink JW. J Histochem Cytochem. 2022;70(1):83-97. doi:10.1369/00221554211062499 13. Zhao A, Zhou H, Yang J, Li M, Niu T. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):71. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01342-6 14. Schvartzman JM, Reuter VP, Koche RP, Thompson CB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(26):12851-12856. doi:10.1073/pnas.1817662116 15. Notarangelo G, Spinelli JB, Perez EM, et al. Science. 2022;377(6614):1519-1529. doi:10.1126/science.abj5104 16. Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, et al. Nature. 2012;483(7390):474-478. doi:10.1038/nature10860 17. Chowdhury R, Yeoh KK, Tian Y, et al. EMBO Reports. 2011;12(5):463-469. doi:10.1038/embor.2011.43 18. Wu N, Yang M, Gaur U, Xu H, Yao Y, Li D. Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 2016;24(1):1-8. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2015.078 19. Urban DJ, Martinez NJ, Davis MI, et al. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12758. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12630-x 20. Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1058-1066. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0903840 21. Makishim a H, Yoshizato T, Yoshida K, et al. Nat Genet. 2017;49(2):204-212. doi:10.1038/ng.3742 22. DiNardo CD, Ravandi F, Agresta S, et al. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(8):732-736. doi:10.1002/ajh.24072 23. Corces-Zimmerman MR, Hong WJ, Weissman IL, Medeiros BC, Majeti R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(7): 2548-2553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324297111 24. Morita K, Wang F, Jahn K, et al. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5327. doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2025.02.003 25.Miles LA, Bowman RL, Merlinsky TR, et al. Nature. 2020;587(7834):477-482. 26. Schwede M, Jahn K, Kuipers J, et al. Leukemia. 2024;38(7):1501-1510. doi: 10.1038/s41375-024-02211-z 27. Sirenko M, Lee S, Sun Z, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2025;32(7):1102-1121 e1105. 28. Bataller A, Kantarjian H, Bazinet A, et al. Haematologica. 2024;109(11):3543-3556. doi:10.3324/haematol.2024.285057. 29. Rapaport F, Neelamraju Y, Baslan T et al. Leukemia. 2021;35(9):2688-2692. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01153-0.