MDS-AML Spectrum

Background on MDS and AML

Background on MDS and AML

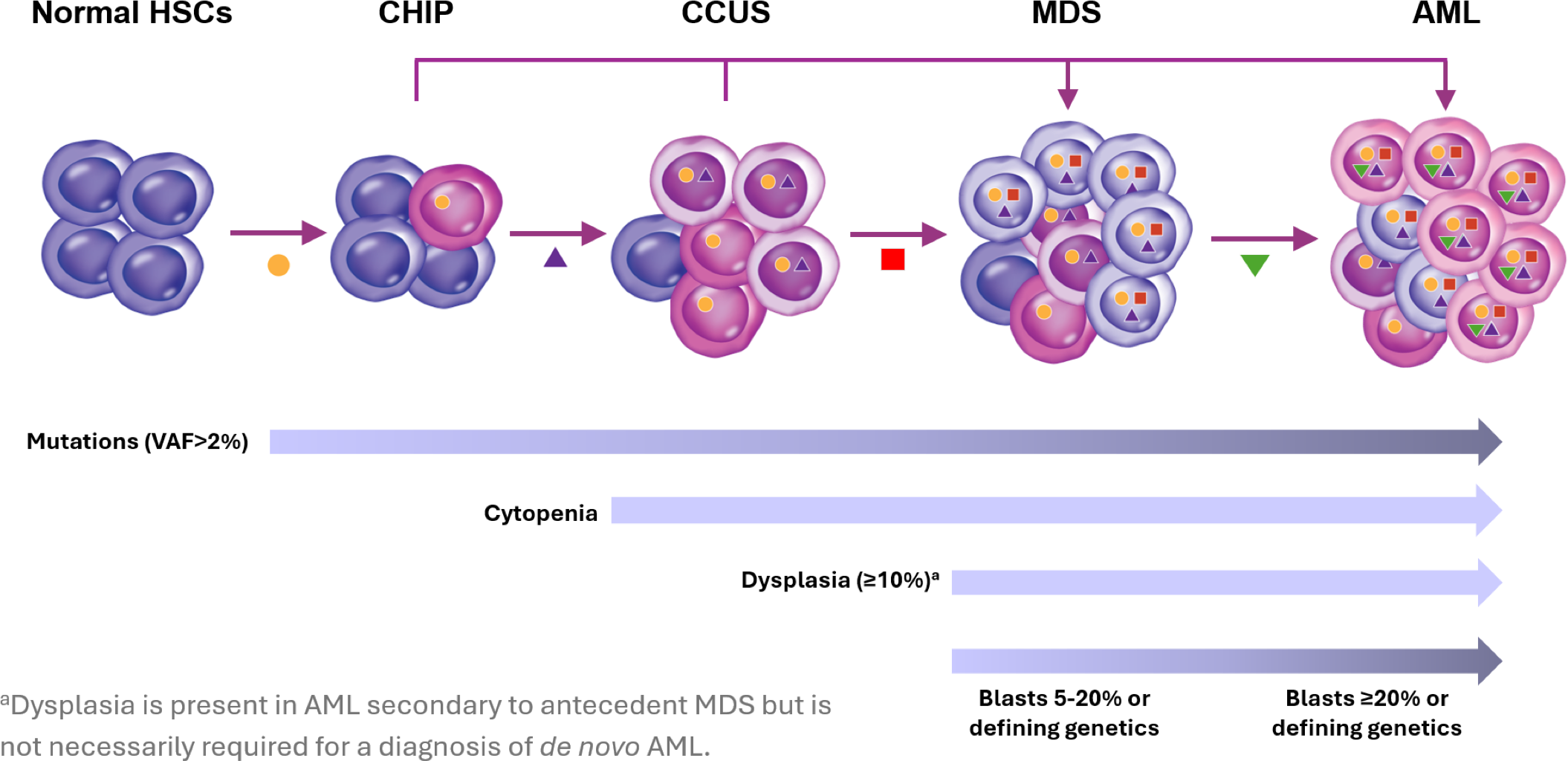

Development of MDS/AML:

Role of Clonal Hematopoiesis, CHIP and CCUS

Development of MDS/AML: Role of Clonal Hematopoiesis, CHIP and CCUS

Relationship of MDS/AML with CHIP and CCUS.11,12

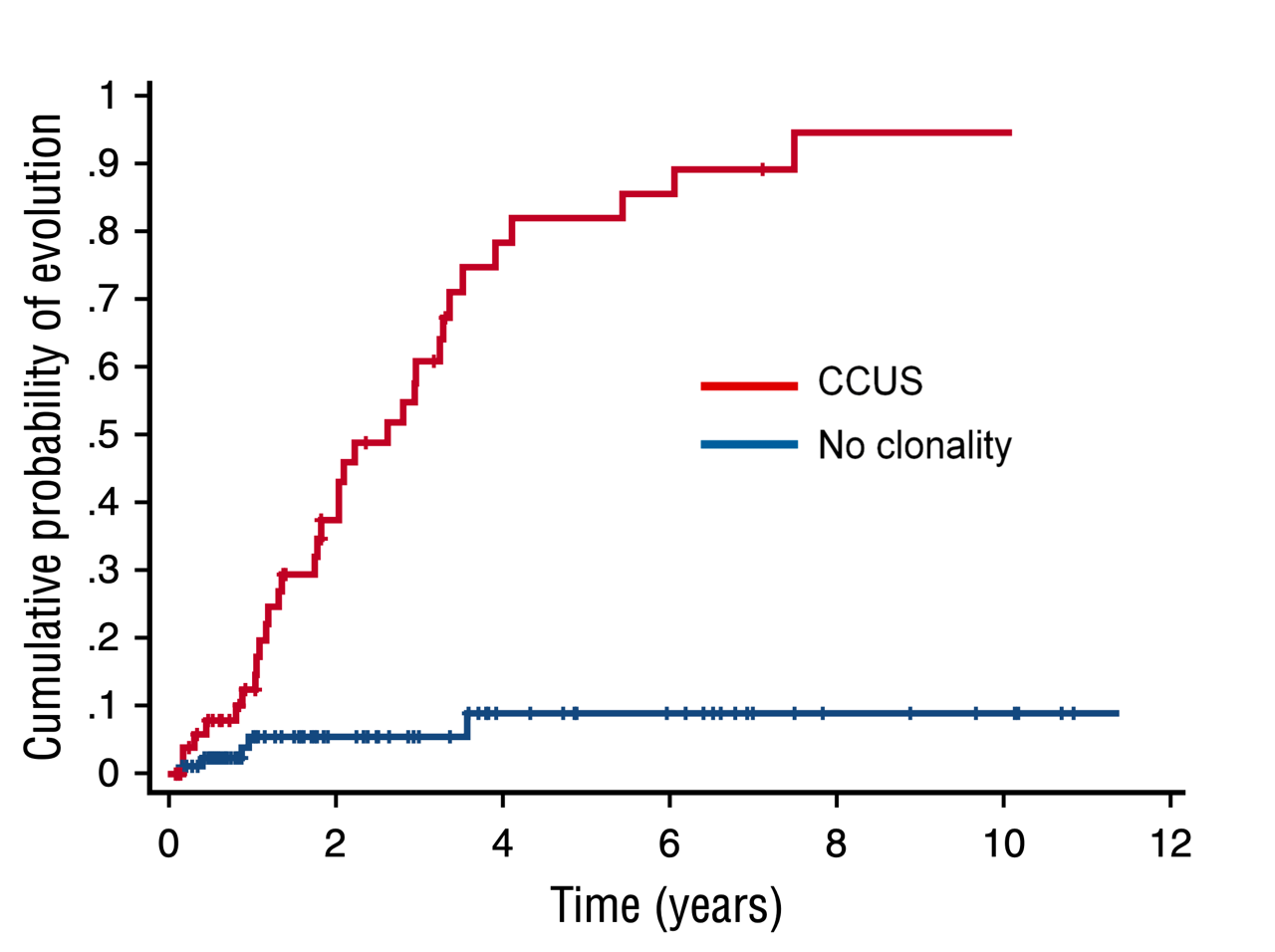

Cumulative probability of myeloid neoplasm in patients who have CCUS vs patients with no clonality.13

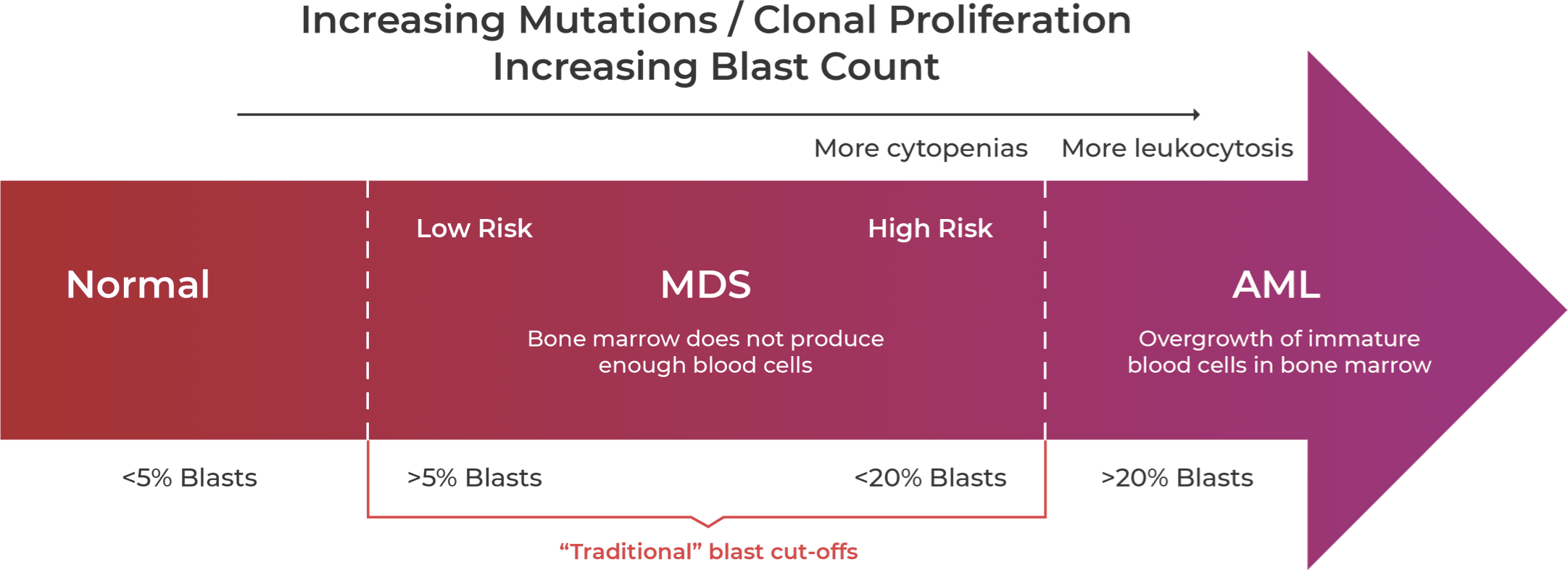

The MDS-AML Spectrum

The MDS-AML Spectrum

As described above, MDS and AML are part of a spectrum of disease resulting from successive acquisition of mutations during clonal hematopoiesis. A spectrum also exists between MDS and AML, with MDS skewing toward dysplasia and ineffective hematopoiesis, and AML skewing toward increased blasts.17,18

Guidelines are relaxing the traditional blast count cut-offs to suggest MDS-AML is more a spectrum of disease.11,12,19,21-23

Acquisition of mutations in stem cells disrupt the normal formation and differentiation of peripheral blood cells19,20 resulting in an increase in blast counts as MDS progresses to AML.11 The blast count cutoff is traditionally defined at 20%; however, guidelines are rapidly changing to reflect the overlap of the two related disease states and to take into account mutational status, which may influence risk stratification.12

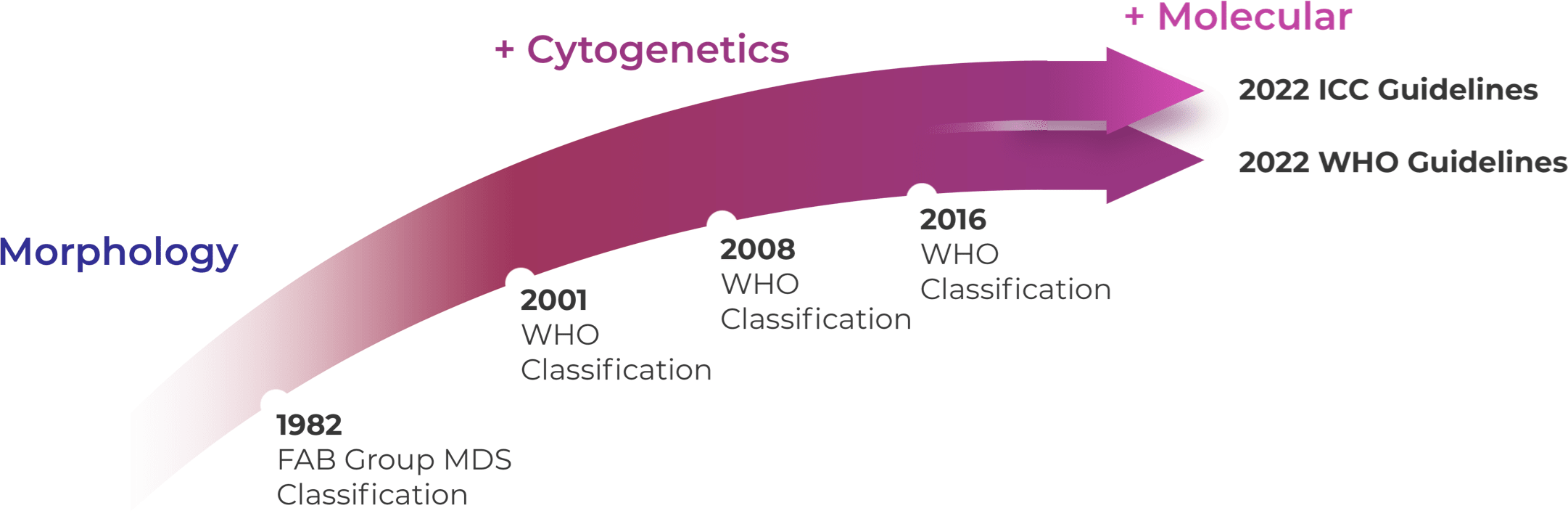

Updated Guidelines Reflect

MDS-AML Spectrum

Updated Guidelines Reflect MDS-AML Spectrum

Recent changes to the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Consensus Classification (ICC) classifications reflect a move away from morphological definition of disease and toward a genetic basis for defining MDS and AML.12,23,24 The ICC has refined the bone marrow blast categories for MDS from <5% to 9% and created a new MDS/AML category for 10%-19% blasts, whereas the WHO categories of MDS-IB2 and MDS-f retain blast counts up to 19%.12,23 WHO 2022 eliminated blast cutoffs for most AML types with defining genetic alterations but retained a 20% blast cutoff to delineate MDS from AML.12 The lowered ICC 2022 blast cutoff suggests both the relevance of genetic alterations and that MDS-AML is a spectrum of disease.23

WHO 2016 and prior WHO classifications were mostly based on morphology and cytogenetics.25 WHO 2022 and ICC 2022 reorganized MDS categories by emphasizing histological and genetic co-variates with slightly different blast categories.12,23,26

Genetic Drivers of

MDS and AML

Genetic Drivers of MDS and AML

Mutated IDH1/2, recurrent genetic drivers, may be expressed in both MDS and AML patients as indicated by genetic profiling.20,27

Hematology studies have shed light on the impact of IDH1/2 mutations in MDS and AML. In MDS, mIDH1 and mIDH2 are considered early “driver” mutations, occurring in approximately 3.6% and 5% of MDS patients, respectively.27-30 As the disease progresses from low-risk MDS to high-risk MDS to AML, the frequency of mIDH1 and mIDH2 in patient populations increases, indicating its role in disease evolution.30-32 mIDH1 and mIDH2 also have been shown to be associated with direct transformation to AML from LR-MDS.33

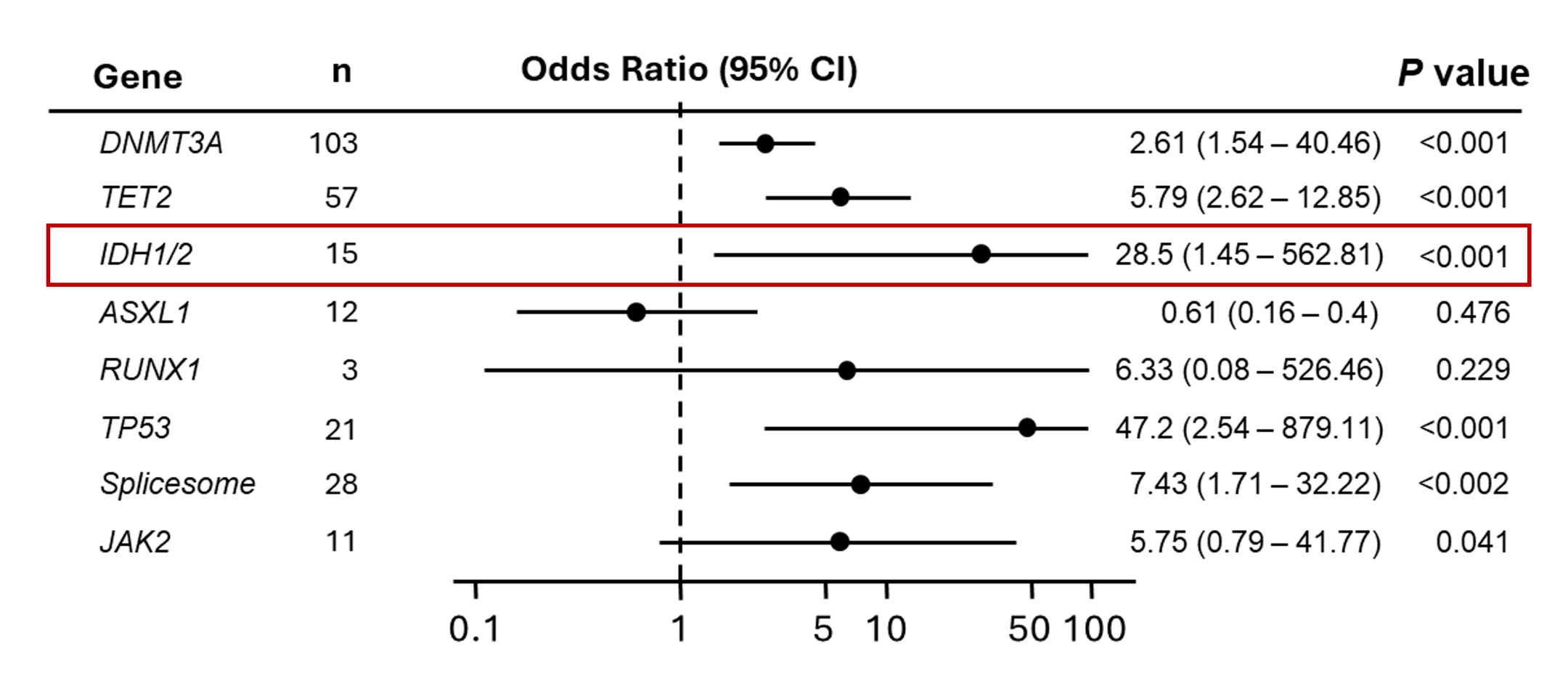

In addition to transformation from MDS to AML, mIDH1 and mIDH2 have been shown to increase transformation to AML in patients who have CHIP. Although mIDH1 and mIDH2 are rare in CHIP, an analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative demonstrated that all 15 healthy subjects who had mIDH1 or mIDH2 at baseline developed AML after a median follow up of 9.6 years.34

Multivariable analysis of the risk to develop AML associated with the presence of mutated genes. Individuals who had an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation at baseline had a 28.5-fold odds of developing AML vs not developing AML.34

Clinical Crossfire: Expert

Discussion on MDS and AML

Clinical Crossfire: Expert Discussion on MDS and AML

Expert Joshua Zeidner, MD discusses recent updates to the ICC and WHO classification of AML and MDS.

Expert Uma Borate, MD discusses the impact of high-risk mutations on MDS to AML progression.

What additional topics in IDH science

would you like to hear about?

What additional topics in IDH science would you like to hear about?

LearnMore about the prognostic impact of mIDH in MDS and AML LearnMore about the prognostic impact of IDH mutations in GliomaStay in the Know

Keep up to date on the latest in

IDH science from leading experts.

References:

1. Klepin HD, Rao AV, Pardee TS. JCO. 2014;32(24):2541-2552. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1564 2. Steensma DP. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(7):969-983. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.001 3. American Cancer Society. About MDS website. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/CRC/PDF/Public/8743.00.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2023. 4. Higgins A, Shah MV. Genes. 2020;11(7):749. doi:10.3390/genes11070749 5. Ye X, Chen D, Zheng Y, Wu C, Zhu X, Huang J. Hematological Oncology. 2019;37(4):438-446. doi:10.1002/hon.2660 6. Montoro J, Vallespi T, Sancho E, et al. Blood. 2011;118(21):5026-5026. doi:10.1182/blood.V118.21.5026.5026 7. Brunner AM, Blonquist TM, Hobbs GS, et al. Blood Advances. 2017;1(23):2032-2040. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010165 8. Nachtkamp K, Stark R, Strupp C, et al. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(6):937-944. doi:10.1007/s00277-016-2649-3 9. Alonso‐Fernandez‐Gatta M, Martin‐Garcia A, Martin‐Garcia AC, et al. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(4):536-541. doi:10.1111/bjh.17652 10. Gaulin C, Kelemen K, Arana Yi C. Life (Basel). 2022;12(8). doi: 10.3390/life12081135. 11. Ambinder AJ, DeZern AE. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1033534. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.1033534 12. Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, et al. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1703-1719. doi:10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1 13. Malcovati L, Galli A, Travaglino E, et al. Blood. 2017;129(25):3371-3378. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-01-763425. 14. Weeks LD, Niroula A, Neuberg D, et al. NEJM Evid. 2023;2(5):10.1056/evidoa2200310. doi: 10.1056/evidoa2200310. 15. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):111-121.10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719. 16. Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488-2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. 17. Chan O, Renneville A, Padron E. Leukemia. 2021;35(6):1552-1562. doi:10.1038/s41375-021-01207-3 18. Mughal TI, Cross NCP, Padron E, et al. Haematologica. 2015;100(9):1117-1130. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.114660 19. Joudinaud R, Boyer T. Front Oncol. 2021;11:730899. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.730899 20. Woll PS, Yoshizato T, Hellström‐Lindberg E. J Intern Med. 2022;292(2):262-277. doi:10.1111/joim.13535 21. Pontrelli G, Loscalzo C, L’Eplattenier M. JAAPA. 2023;36(6):17-21. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000931428.87936.72 22. Bewersdorf JP, Zeidan AM. Cells. 2020;9(10):2310. doi:10.3390/cells9102310 23. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, et al. Blood. 2022;140(11):1200-1228. doi:10.1182/blood.2022015850 24. Huber S, Baer C, Hutter S, et al. Blood. 2022;140(Supplement 1):555-556. doi:10.1182/blood-2022-162326 25. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391-2405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544 26. Zeidan AM, Pollyea DA, Garcia JS, et al. Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):565-565. doi:10.1182/blood-2019-124994 27. DiNardo CD, Jabbour E, Ravandi F, et al. Leukemia. 2016;30(4):980-984. doi:10.1038/leu.2015.211 28. Thol F, Weissinger EM, Krauter J, et al. Haematologica. 2010;95(10):1668-1674. doi:10.3324/haematol.2010.025494 29. Medeiros BC, Fathi AT, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, Chan SM, Swords R. Leukemia. 2017;31(2):272-281. doi:10.1038/leu.2016.275 30. Testa U, Castelli G, Pelosi E. Cancers. 2020;12(9):2427. doi:10.3390/cancers12092427 31. Makishima H, Yoshizato T, Yoshida K, et al. Nat Genet. 2017;49(2):204-212. doi:10.1038/ng.3742 32. Molenaar RJ, Thota S, Nagata Y, et al. Leukemia. 2015;29(11):2134-2142. doi:10.1038/leu.2015.91 33. Jain AG, Ball S, Aguirre L, et al. Haematologica. 2024; 109(7):2157-2164. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2023.283661. 34. Desai P, Mencia-Trinchant N, Savenkov O, et al. Nat Med. 2018;24(7):1015-1023. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0081-z.