The Importance of

Mutational Testing

Molecular testing can provide comprehensive and meaningful prognostic information. In this era of personalized patient care, advances in mutational testing have improved access to molecular data for diagnosis, risk stratification and clinical decision-making.1

Several gene mutations have been identified among patients with MDS that may, in part, contribute to the clinical heterogeneity of the disease course, and thereby influence the prognosis of patients.2 Molecular testing is recommended as part of the initial evaluation for MDS.2

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) have also evolved over time to incorporate molecular mutations into risk stratification (along with morphology and cytogenetics) and to emphasize the need to expedite mutational testing results for mutations including IDH1 and IDH2.1

Many testing laboratories have improved turnaround times, in some cases to a few days, and real-world data suggests that a delay of a week or two in obtaining genetic testing results had no negative impact on patient outcomes.3–8,10,11

A Short Wait for Testing Has No

Impact on Outcomes

A Short Wait for Testing Has No Impact on Outcomes

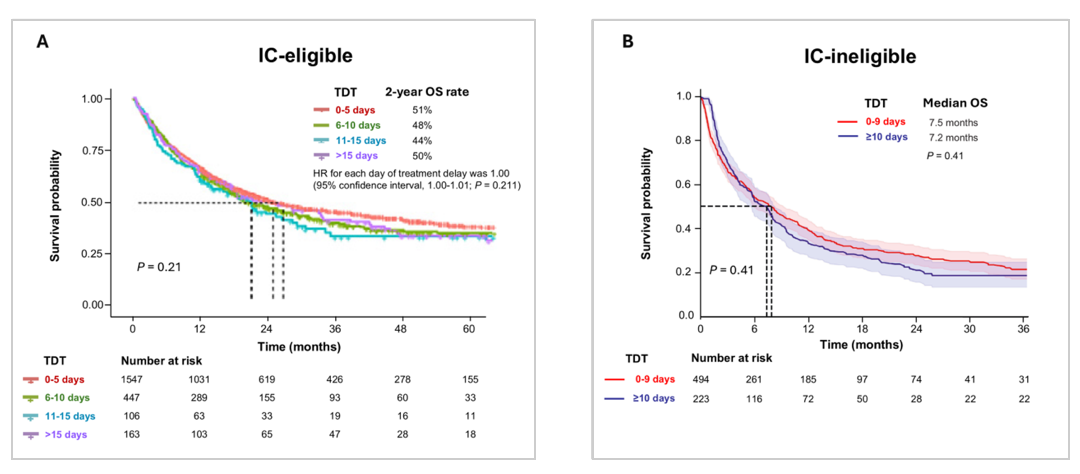

Two large studies utilizing real-world data explored the impact of a short delay for testing on patient outcomes. A study by Rollig et al. analyzed patients from the Study Alliance Leukemia [SAL] database (N=2263) with newly-diagnosed AML who did not require immediate action (e.g., leukostasis), and were eligible for intensive induction chemotherapy.5 The results revealed that a short wait for mutational testing to personalize AML management had no adverse effect on overall survival (OS) or remission rates.5 Patients were categorized based on the time from diagnosis to treatment start (TDT) ̶ 0-5 days, 6-10 days, 11-15 days, or ˃15 days.5 The 2-year OS (unadjusted) for each TDT group was 51%, 48%, 44%, and 50%, respectively, with no significant differences between the groups (Figure A below).5 Furthermore, there were no significant differences in OS when stratified for age (up to 60 years vs. over 60 years) or white blood cell count (low vs. high).5

Similar results were reported in a study by Baden et al., which evaluated a short delay in treatment in patients with newly-diagnosed AML who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy and received less intensive regimens.6 Patients were enrolled from 2 cohorts (the SAL database [N=138] and the global health network TriNetX [N=717]) and were stratified according to a TDT of 0-9 days or a TDT of ≥10 days. No significant differences in median OS were observed between the TDT 0-9 and TDT ≥10 groups, neither in the SAL cohort (7.7 vs. 9.6 months, respectively; P=0.42) nor in the TriNetX cohort (7.5 vs. 7.2 months, respectively; P=0.41; Figure B below). Additionally, subgroup analysis in both cohorts demonstrated no significant differences in median OS between the two TDT groups among patients who were aged ≥75 years or who had a low white blood cell count. These studies suggest that a slight pause to determine the best course of action in AML management may be a viable option that does not negatively impact patient outcomes.5,6

Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS according to TDT groups. (A) IC-eligible patients5 (B) IC-ineligible patients who received less intensive regimens (data are from the TriNetX cohort).6

The Beat AML Master trial further validated the idea that taking time for mutational testing can optimize the management of AML.7 In this trial, mutational testing was conducted within seven days to customize care based on individual mutational results.7 The study found that a seven-day delay to perform detailed molecular testing did not negatively impact mortality and overall survival rates.7

These findings reiterate that a short wait for mutational testing can be safely implemented to determine a personalized management approach for AML patients.7

Taking a slight pause to determine the best course of

action in AML management may be a viable option

without negatively impacting patient outcomes.5-7

NCCN Guidelines®

Recommendations in AML

NCCN Guidelines® Recommendations in AML

The recent NCCN Guidelines in AML underscore the critical importance of expediting mutational testing results at diagnosis, including cases involving potential IDH1 or IDH2 mutations.1

Molecular Profiling Is Part of the Standard Workup as Several Gene Mutations Can Affect Prognosis

“Identification of mutations that carry prognostic and therapeutic impact is rendering molecular profiling for all AML cases a standard part of the diagnostic workup. In addition to basic cytogenetic analysis, new molecular markers can help refine prognostics groups, particularly in the setting of a normal karyotype.”1

“Multi-gene molecular profiling/targeted NGS (including IDH1/IDH2, FLT3 mutations) is suggested…Molecular testing should be repeated at each relapse or progression.”1

Expedite Testing at Diagnosis for Immediately Actionable Mutations While Adding Disease Control

“…Test results of molecular and cytogenetic analyses of immediately actionable genes or chromosomal abnormalities should be expedited.”1

For patients with uncontrolled hyperleukocytosis, systemic therapy for disease control may be considered prior to receiving diagnostic results1

Expanded Availability of Commercial Mutational Testing Labs

“Tests for these molecular markers are now available in commercial reference laboratories and in referral centers. Therefore, it is important for physicians to confer with the local pathologist on how to optimize sample collection from the time of diagnosis for subsequent molecular diagnostic tests.”1

NCCN Guidelines

Recommendations in MDS

NCCN Guidelines Recommendations in MDS

Mutational testing is recommended as part of the initial evaluation for MDS, and includes testing for IDH1 and IDH2 mutations.2

“Genetic testing for somatic mutations (i.e., acquired mutations) in genes associated with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)” is recommended as part of the initial evaluation.2

“Reevaluation with bone marrow and/or molecular testing is recommended.”2a

Despite recommendations, not all AML and MDS patients receive the needed tests, especially in the community setting.9,10

Given the diversity of mutations impacting MDS and AML, accurate assessment of each patient’s genotype is crucial for making informed clinical decisions.1 While full NGS sequencing can be used for this analysis, rapid tests that provide results in a few days may also be available, offering valuable information for personalized patient care.3,4,8,10,11

Clinical Crossfire: Expert

Discussion on Molecular Testing

Clinical Crossfire: Expert Discussion on Molecular Testing

Expert Joshua Zeidner, MD and Uma Borate, MD discuss how to talk to a patient about waiting for testing results

Expert Joshua Zeidner, MD and Uma Borate, MD discuss the NCCN Guidelines on mutational testing

What additional topics in IDH science

would you like to hear about?

What additional topics in IDH science would you like to hear about?

Stay in the Know

Keep up to date on the latest in

IDH science from leading experts.

aGenerally after no response, intolerance or relapse in lower- and higher-risk MDS.

References:

1. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Acute Myeloid Leukemia V.2.2025. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2025. All rights reserved. Accessed May 20, 2025. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. 2. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Myelodysplastic Syndromes V.2.2025. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2025. All rights reserved. Accessed May 20, 2025. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. 3. Duncavage EJ, et al. Blood. 2022;140(21):2228-2247. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015853 4. Megías-Vericat JE, Ballesta-López O, Barragán E, Montesinos P. BLCTT. 2019; 9:19-32. doi:10.2147/BLCTT.S177913 5. Röllig C, Kramer M, Schliemann C, et al. Blood. 2020;136(7):823-830. doi:10.1182/blood.2019004583 6. Baden D, Zukunft S, Hernandez G, et al. Haematologica. 2024;109(8):2469-2477. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2024.285225. 7. Burd A, Levine RL, Ruppert AS, et al. Nat Med. 2020;26(12):1852-1858. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1089-8 8. Nelson EJ, et al. Mol Diagn Ther. 2023;27:371-381. doi: 10.1007/s40291-022-00638-7. 9. Lin TL, Williams T, He J, et al. Cancer Med. 2015;4(4):519-522. doi:10.1002/cam4.406 10. Pollyea DA, George TI, Abedi M, et al. eJHaem. 2020;1(1):58-68. doi:10.1002/jha2.16 11. Guijarro F, et al. Curr. Oncol. 2023;30:5201-5213. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30060395

NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.