The Importance of

Mutational Testing

Molecular testing can provide comprehensive and meaningful prognostic information. In this era of personalized patient care, advances in mutational testing have improved access to molecular data for diagnosis, risk stratification and clinical decision-making.1

Several gene mutations have been identified among patients with MDS that may, in part, contribute to the clinical heterogeneity of the disease course, and thereby influence the prognosis of patients.2 Molecular testing is recommended as part of the initial evaluation for MDS.2

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) have also evolved over time to incorporate molecular mutations into risk stratification (along with morphology and cytogenetics) and to emphasize the need to expedite mutational testing results for mutations including IDH1 and IDH2.1

Many testing laboratories have improved turnaround times in some cases to a few days, but real-world data suggests that a delay of a week or two had no impact on patient outcomes.3–7,9,10

A Short Testing Delay Has No

Impact on Outcomes

A Short Testing Delay Has No Impact on Outcomes

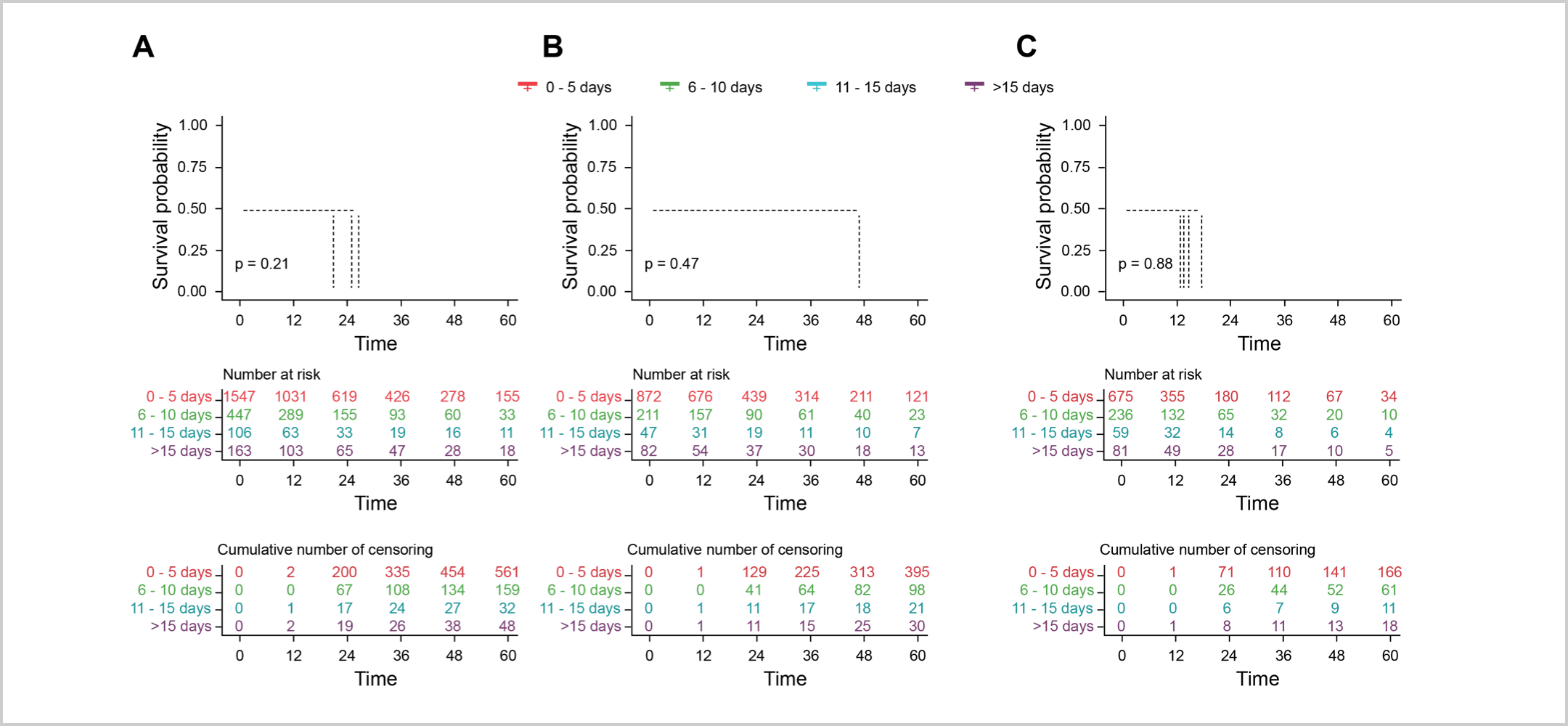

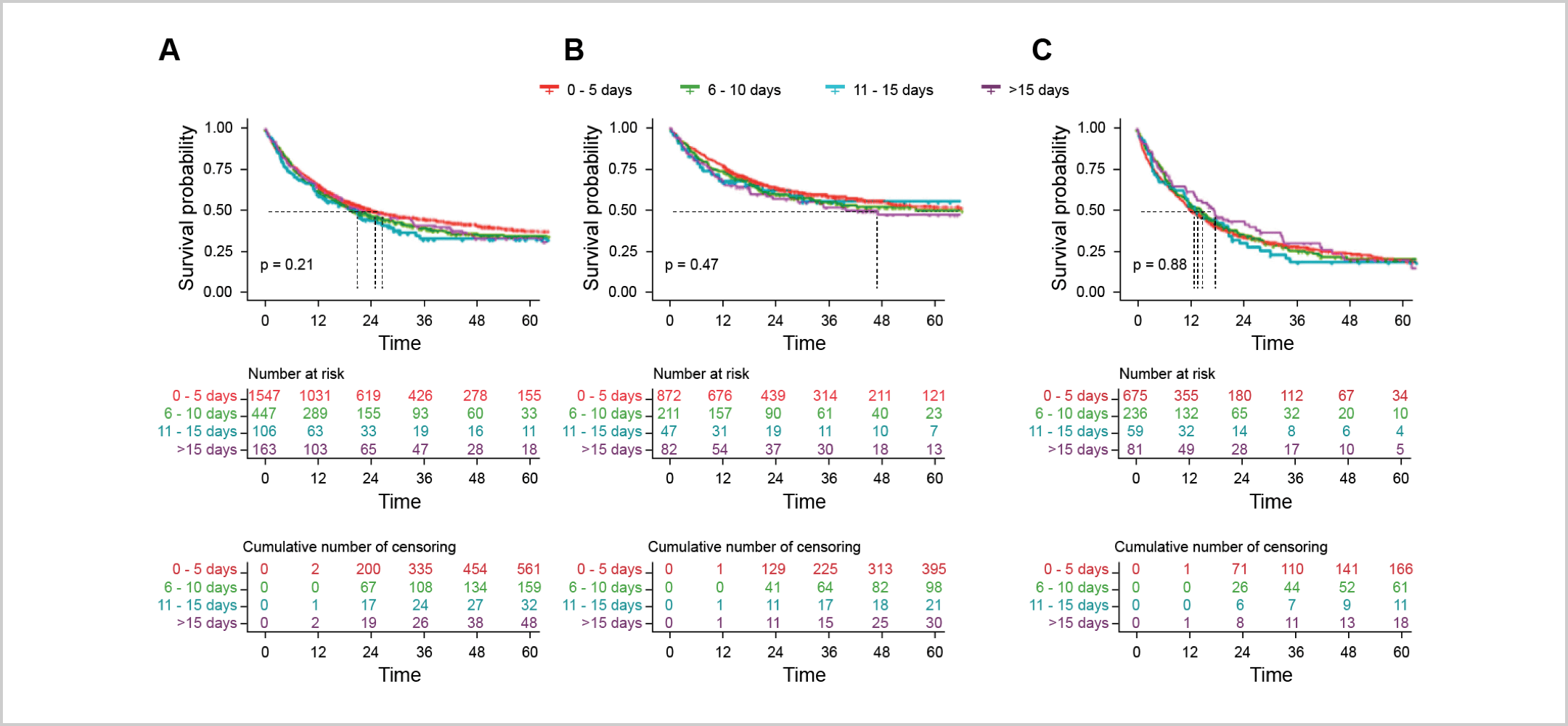

A large trial utilizing real-world data explored the impact of a short delay for testing on patient outcomes in cases of AML that do not require immediate action, i.e., leukostasis.5 The results revealed that a short delay for mutational testing to personalize AML management had no adverse effect on patient survival or remission rates.5 Patients were categorized based on the time from diagnosis to treatment start (TDT) – 0-5 days, 6-10 days, 11-15 days, or >15 days.5 The 2-year overall survival (unadjusted) for each TDT group was 51%, 48%, 44%, and 50%, respectively, indicating no significant differences between the groups.5 Furthermore, there were no significant differences in overall survival, even when stratified for age (up to 60 years vs. over 60 years) or white blood cell count (low vs. high).5 This suggests that taking a slight pause to determine the best course of action in AML management may be a viable option without negatively impacting patient outcomes.5

“Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS according to TDT groups. (A) All patients. (B) In patients ≤60 years. (C) In patients >60 years.”5

The Beat AML Master trial further validated the idea that taking time for mutational testing can optimize the management of AML.6 In this trial, mutational testing was conducted within seven days to customize care based on individual mutational results.6 The study found that a seven-day delay to perform detailed molecular testing did not negatively impact mortality and overall survival rates.6

These findings reiterate that a short delay for mutational testing can be safely implemented to determine a personalized management approach for AML patients.6

Taking a slight pause to determine the best course of

action in AML management may be a viable option

without negatively impacting patient outcomes.5,6

NCCN Guidelines®

Recommendations in AML

NCCN Guidelines® Recommendations in AML

The recent NCCN Guidelines in AML underscore the critical importance of expediting mutational testing results at diagnosis, including cases involving potential IDH1 or IDH2 mutations.1

Molecular Profiling Is Part of the Standard Workup as Several Gene Mutations Can Affect Prognosis

“Identification of mutations that carry prognostic and therapeutic impact is rendering molecular profiling for all AML cases a standard part of the diagnostic workup. In addition to basic cytogenetic analysis, new molecular markers can help refine prognostics groups, particularly in the setting of a normal karyotype.”1

“Multi-gene molecular profiling/targeted NGS (including IDH1/IDH2, FLT3 mutations) is suggested…Molecular testing should be repeated at each relapse or progression.”1

Expedite Testing at Diagnosis for Immediately Actionable Mutations While Adding Disease Control

“…Test results of molecular and cytogenetic analyses of immediately actionable genes or chromosomal abnormalities should be expedited.”1

For patients with uncontrolled hyperleukocytosis, systemic therapy for disease control may be considered prior to receiving diagnostic results1

Expanded Availability of Commercial Mutational Testing Labs

“Tests for these molecular markers are now available in commercial reference laboratories and in referral centers. Therefore, it is important for physicians to confer with the local pathologist on how to optimize sample collection from the time of diagnosis for subsequent molecular diagnostic tests.”1

NCCN Guidelines

Recommendations in MDS

NCCN Guidelines Recommendations in MDS

Mutational testing is recommended as part of the initial evaluation for MDS, and includes testing for IDH1 and IDH2 mutations.2

“Genetic testing for somatic mutations (i.e., acquired mutations) in genes associated with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)” is recommended as part of the initial evaluation.2

“It is recommended to repeat molecular testing to identify targetable mutations.”2a

Despite recommendations, not all AML and MDS patients receive the needed tests, especially in the community setting.8,9

Given the diversity of mutations impacting MDS and AML, accurate assessment of each patient’s genotype is crucial for making informed clinical decisions.1 While full NGS sequencing can be used for this analysis, rapid tests may also be available in a few days, offering valuable information for personalized patient care.3,4,7,9,10

Clinical Crossfire: Expert

Discussion on Molecular Testing

Clinical Crossfire: Expert Discussion on Molecular Testing

Expert Joshua Zeidner, MD and Uma Borate, MD discuss how to talk to a patient about waiting for testing results

Expert Joshua Zeidner, MD and Uma Borate, MD discuss the NCCN Guidelines on mutational testing

What additional topics in IDH science

would you like to hear about?

What additional topics in IDH science would you like to hear about?

Stay in the Know

Keep up to date on the latest in

IDH science from leading experts.

a at relapse after allo-HCT in patients with higher-risk MDS

References:

1. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Acute Myeloid Leukemia V.3.2024. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2024. All rights reserved. Accessed June 14, 2024. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. 2. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Myelodysplastic Syndromes V.3.2024. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2024. All rights reserved. Accessed July 25, 2024. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. 3. Duncavage EJ, et al. Blood. 2022;140(21):2228-2247. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015853 4. Megías-Vericat JE, Ballesta-López O, Barragán E, Montesinos P. BLCTT. 2019; 9:19-32. doi:10.2147/BLCTT.S177913 5. Röllig C, Kramer M, Schliemann C, et al. Blood. 2020;136(7):823-830. doi:10.1182/blood.2019004583 6. Burd A, Levine RL, Ruppert AS, et al. Nat Med. 2020;26(12):1852-1858. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-1089-8 7. Nelson EJ, et al. Mol Diagn Ther. 2023;27:371-381. doi: 10.1007/s40291-022-00638-7. 8. Lin TL, Williams T, He J, et al. Cancer Med. 2015;4(4):519-522. doi:10.1002/cam4.406 9. Pollyea DA, George TI, Abedi M, et al. eJHaem. 2020;1(1):58-68. doi:10.1002/jha2.16 10. Guijarro F, et al. Curr. Oncol. 2023;30:5201-5213. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30060395

NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.